In the rapid expansion of basketball analytics, coaches have faced a barrage of new statistics. The information can be overwhelming, and coaches don’t always have the time to research and reflect on the value of each new metric. One statistic to pay close attention to, in my opinion, is the characterization of whether or not each shot attempt is open.

Regardless of a team’s offensive system, every coach wants open shots. Whether it’s a Kyle Korver 3 or a LeBron drive, if it’s open, it’s better.

When we scan the NBA, the percent of open looks that players experience can vary wildly. Carmelo Anthony and Ryan Anderson are both considered great NBA shooters. Why is it that only 46% of Carmelo’s jumpers were open when 93% of Anderson’s were? When it comes to interpreting these numbers, there are 4 factors to consider.

- The first factor is the quality of the shooter. The better the shooter, the fewer open shots they are likely to get. 94% of Andre Roberson’s jumpers (from greater than 10ft) were open because he only makes 25% of them. Only 50% of C.J. McCollum’s jumpers were open because he makes 50% of his. Defenses are happy to let a weak shooter like Roberson bomb away, especially if it means his teammate Russell Westbrook doesn’t have a clear path to the hoop. In contrast, defenses never want to leave a sharpshooter like McCollum open on the perimeter.

- The second factor is player choice. Anderson is not going to take his man off the dribble and pull up in the midst of a double team. He’s not going to force such a tough shot for two reasons. First, he’s not very efficient at them. Second, and more importantly, he’s a supplemental piece in an offense run through James Harden.

In every NBA team, there is a hierarchy of offensive options. Imagine that the game is tied with 20 seconds on the clock in Game 7 of the NBA Finals. Cleveland’s Dahntay Jones receives the inbounds. To his left, Kyrie Irving is calling for the ball. Jones brushes him off. To his right, LeBron James is pleading for a pass. Jones ignores him. He puts his head down and takes on a double team as he attempts to get to the hoop.

The above scenario sounds absurd because Jones hasn’t earned the right to take the game into his hands. If he did, it would be like the bus boy at a restaurant declaring all meals on the house.

In contrast, as the perceived alpha in New York, Carmelo Anthony is more than willing to force difficult shots even though he also isn’t efficient at them.

Under the umbrella of player choice, the extent to which a player uses the mid-range is often indicative of how open they are. 3-point shots are open more often than mid-range jumpers. Most often, shooters get open when their defender helps near the rim. Mid-range shots are closer to the rim and easier to recover to. Shaun Livingston lives on mid-range attempts, and thus, only 21% of his jumpers were open. Eric Gordon almost never takes a shot from mid-range, and thus, 85% of his jumpers were open.

Of course, the decision to dribble into a contested mid-range jumper is not usually a good one. D’Angelo Russell averaged 1.13 points when he caught and shot a 3 (without dribbling). He averaged 0.77 points per 2-point attempt that he dribbled into. In other words, he generated 3.6 more points for 10 catch-and-shoot threes than 10 pull-up mid-range jumpers. In spite of this, Russell took more pull-up 2s than catch-and-shoot 3s each game.

- The third major factor is the star’s impact. Great players attract help defense that frees up their teammates. Kyle Korver has been knocking down threes in the NBA for 13 years. Every NBA team schemes to take away his shot. And Korver’s efficiency is impacted by the level to which his attempts are contested. Korver shot 38% from 3 when contested and 49% when open. When he was wide-open (no defender was within 6 feet), Korver shot an outstanding 55%.

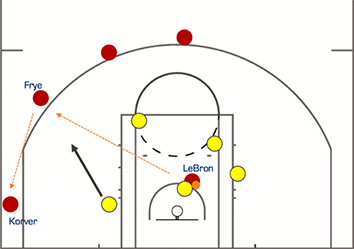

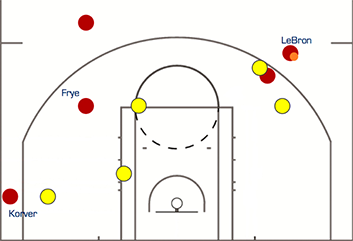

Fortunately for Korver, he now plays with LeBron James. Consider the following example from their game against Indiana on February 15, 2017. In the first image, LeBron comes off a screen above the break as Korver and Channing Frye wait on the weak side.

Next, LeBron beats his man, as he so often does. Help defense comes from Frye’s man. LeBron kicks to Frye. This forces Korver’s man to switch and challenge Frye. Frye finds the open Korver in the corner.

Korver’s open shot was a result of good play design, quality passing, and most importantly, the brilliance of LeBron James.

- The last factor in creating open shots is the one where coaches have the most influence. It is player and ball movement. Every team can get more open looks by moving the ball, setting good screens, and in general, executing a well-designed offense.

The Golden State Warriors are the golden standard for ball and player movement in the NBA. Their players held the ball an average of 2.43 seconds every time they touched the ball, the 2nd lowest mark in the NBA. They led the league in the stat the last 2 seasons.

The Warriors also led the league with 30.4 assists per game (over 5 more than any other team). But perhaps the most telling stat in regards to their ball movement is their secondary assists per game. These are the so-called hockey assists; they are the pass before the assist when the assisting player catches and moves the ball immediately. In other words, secondary assists occur when two quick passes lead to a made basket. The Warriors averaged 9.6 secondary assists per game, about 3 more than any other team.

Coach’s Takeaway

Coaches want their teams to get open shots. The first step to improving on this metric is knowing where a team currently stands, however manually tracking open and contested shots is tedious at best. When done by humans, it’s subjective; what one tracker thinks is open, another might think is contested. ShotTracker TEAM is a new technology that makes it easy to consistently capture this data in real-time, during practices or games. To assess the “why” behind the data, coaches must analyze the four major factors that lead to open shots: player shooting ability, player shot selection, star impact, and player and ball movement.